Data protection law continues to make headlines in the time of Corona: Lawyers, politicians and computer scientists are engaged in a public debate about what can, may and must be possible in an emergency situation such as the current one.

Use of Radio Cell Data “Acceptable Under Data Protection Law”

The main issue being discussed is the tracing of infected persons by means of smartphone location data. Through this method, potential infection chains could be uncovered and those already infected could be identified and notified. A matching amendment to the law brought forward by Health Minister Jens Spahn failed before it came to a vote – due to resistance by the Ministry of Justice.

Explaining his Proposal, Spahn claimed that this method had already worked well in South Korea. He did however not care to mention that no individual location data was processed in South Korea. Only radio cell data, i.e. information on how many telephones were connected to which radio tower and when, is processed. But this is also already being practiced in Germany – in full compliance with data protection laws.

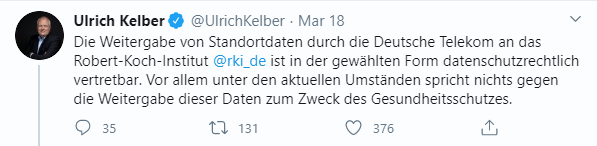

The “Robert-Koch-Institut” (RKI), Germany’s authority on fighting the pandemic, has been using the cell tower location data of a stunning 46 million users, supplied by Deutsche Telekom, in an aggregated format to predict the spread of the disease. On Twitter, Federal Data Protection Commissioner Ulrich Kelber called this method “justifiable under Data Protection Law“. Read his original tweet in German here:

Could We Create a “Diffuse, Threatening Feeling of Being Observed”?

Kelber might very well be correct: The use of anonymised location data would be lawful in any case, since the scope of Data Protection Law does not extend to this kind of data in the first place: in aggregated cell phone tower data, no “personal” data within the meaning of Art. 4 No. 1 GDPR is processed at all. However, truly “anonymous” data in the legal sense of the term, is hard to come by, and counts as such only if the inference to an individual person is completely impossible – an extremely high legal and technical standard. Accordingly, Kelber had to put up with scepticism and criticism on Twitter. Marit Hansen, the data protection commissioner of Schleswig-Holstein, also urges that despite the fast pace of political development in the crisis, proportionality must be the foremost concern.

Ever since the heated debate on police surveillance through data retention a few years ago, the phrase “radio cell interception” has data protectionists and civil rights activists on high alert – and rightly so: the Federal Constitutional Court already stated in its ruling on data retention in 2010 that fundamental rights of citizens are not only threatened by their direct surveillance, but already by the fact that one could be observed at any moment: This would create a “diffuse, threatening feeling of being observed, […] which can impair an unbiased perception of fundamental rights in many areas”, the court argued. This seems to be the concern of many citizens and privacy activists who warn of the dangers of mass processing of location data during these hectic times.

New Approach From Singapore and Israel: “Voluntary Self-Regulation”?

A completely novel method is being employed by Singaporian authorities: The App “TraceTogether” was published on March 25 and represents a newway of tracking infected and at-risk persons:

Concept of the TraceTogether-App. Source: https://www.tech.gov.sg/.

Instead of GPS tracking via satellite (or by even less precise radio cell data), the app relies on the Bluetooth sensor built into every smartphone to determine its relative proximity to other devices. This has the of working underground as well as in urban areas such as Singapore or other large cities. If two devices have installed the app and activated Bluetooth, they only send each other four pieces of data when they make contact: Time, Bluetooth signal strength, smartphone model number, and an ID.

This is not anonymous data, of course, as it can be used to draw conclusions about the person behind the ID. This “deanonymizability” of the data is part of the app’s design: If a user is infected with the virus, he should report it to the Ministry of Health, which will then compare the app’s connection data and inform “affected” users, i.e. those who were in the vicinity of the infected person just a short time ago.

Processing Without Consent? Art. 9 GDPR to the Rescue

The issue is further complicated by the fact that the health-related data in question enjoys heightened protection as a “special category” under GDPR: According to Art. 9 Para. 1 GDPR, the processing of such data is, in principle, prohibited. Exceptions can be made when explicit consent with a specified purpose is given (Art. 9 Para. 2 lit. a). The voluntariness of the consent is a decisive point in this question. It must also be ensured that the purpose of processing is not retroactively altered or expanded.

A justification according to Art. 9 Para. 2 lit. i) GDPR also seems possible: instead of (revocable) consent, this would also allow for data processing “for reasons of public interest in the area of public health, such as protecting against serious cross-border threats to health“. However, this section of the GDPR contains an “opening clause”; it still needs to be fleshed out in detail by national law. Germany has done so through Section 22 (1) No. 1 c) Federal Data Protection Act (BDSG) – with the same wording as above. Nevertheless, the processing must always be “necessary”, i.e. in particular suitable and comparatively un-intrusive – this regularly represents a high standard in legal terms. Commissioner Kelber does not consider non-anonymised location data to be suitable for the fight against the corona pandemic: After all, he argues, it only shows the location of the mobile phone itself, and not necessarily that of its owner.

Is Germany Following in the Footsteps of Singapore, Israel, or Will It Chart Its Own Path?

In Germany, too, the way seems to be clear for the use of an app like TraceTogether that is based on voluntary sharing of data (according to data protection law). Therefore, the political impulse seems to go in this direction. However, the benefits and social acceptance of such an app will still have to be evaluated.

Singapore now plans to publish the algorithm behind the app under an open source license, and a similar app is also being used in Israel: “HaMagen” (“the shield”) warns the user if his path has crossed with a corona infected person. This app also does not rely on voluntary information provided by the user, but on location data from the Ministry of Health. This seems to have been implemented contrary to data protection concerns, something Jens Spahn recently failed to do.

Update (2. April): The “Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing”-Initiative

Meanwhile, a consortium of 130 European companies and public institutions has launched the “PEPP-PT”-Initiative: Following the same principle as TraceTogether (voluntary comparison of Bluetooth signal strengths of App users), the to-be-programmed app’s aim is to counteract the spread of the corona virus in Europe – with European data protection standards as a benchmark, in line with the chosen motto: “Proximity Tracing YES, Giving Up Privacy NO!”

The working principle of the app focuses on data minimisation (Art. 5 Para. 1 lit. c GDPR) and encryption: smartphones will only exchange data with each other when they have been in close contact with each other for an “epidemiologically relevant period of time” – and even then, the transmitted data (an app-specific ID) is stored locally encrypted after transmission. Not even the smartphone user has access to his or her own “contact history”. The health authorities, too, should only be able to send a push message to the user’s “contact persons” by means of a TAN-based confirmation sent to the (infected) user.

The PEPP-PT approach goes the extra mile to consistently implement European data protection standards – at least conceptually. It remains to be seen when the app will be available and whether it will prove itself in everyday use.